A talk prepared for the Relleu cultural group Aurora on 20 June 2024 by Gareth Thomas Weaver

Introduction

Donkeys played a central role in Spanish life until the mid-20th century. In agriculture they could be seen ploughing fields or circling the village threshing pan. They transported sacks of grain and pulled wooden carts. In towns donkeys delivered fresh water, fruit and vegetables, and brought goods to the weekly market. Country houses in winter had stables for donkeys on the ground floor, to warm the upper floors with their body heat – you can see this today in the preserved house in the Finestrat museum – and every day people met donkeys in normal life.

This donkey presence in Spanish life is still within living memory. I count myself as part of that memory. When I went to school on my bicycle in Ibiza in the 1960s I cycled past the lines of donkey carts on their way to market in Ibiza town. In the old shipbuilders yard in Ibiza harbour – the astilleros – donkeys used to turn the winch that raised fishing boats out of the water and up the wooden ramp to be repaired. Every farmhouse had a donkey standing in the yard, ready for work.

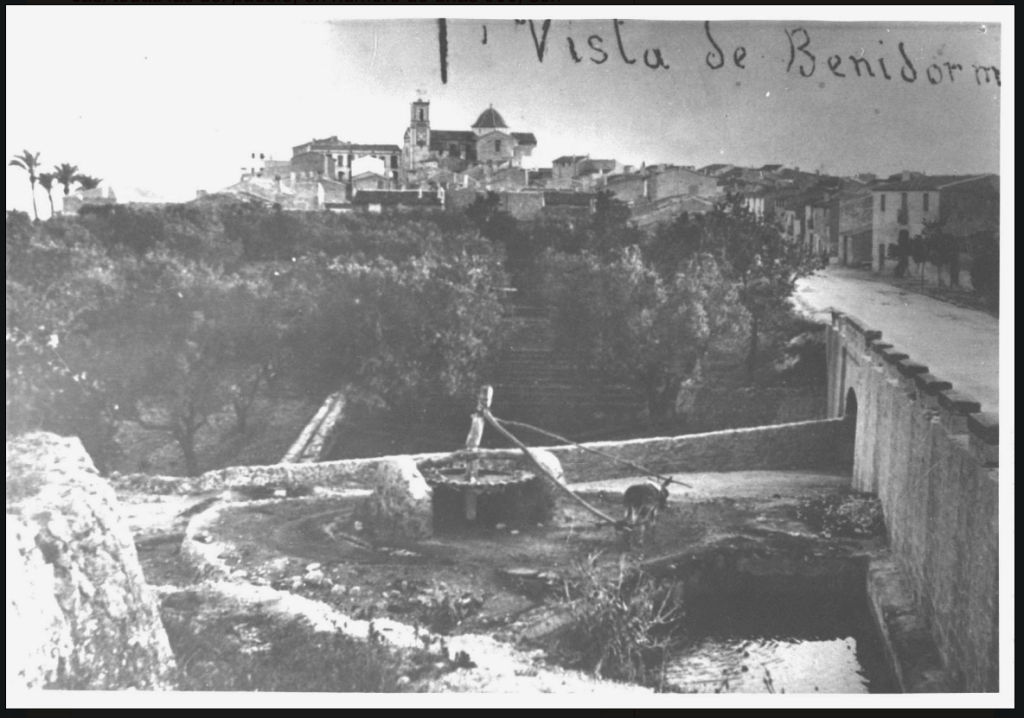

The irrigation systems of Spain also relied on donkeys walking in circles around a noria, the islamic technology from north Africa, used to raise water from wells. The photo here shows the last one in Benidorm in the 1960s. This last donkey-driven noria was next to the bridge by the barranco. Today this site – near the ayuntamiento – is an office of Banco Sabadell by the new bridge in Calle Puente.

Now donkeys have largely disappeared and only kept by enthusiasts, like these you have seen today. When I take my donkeys into Orxeta village, older people comment on them and express their nostalgia, because donkeys were once a normal everyday presence. My donkey Matilde belongs to the endangered breed of Andalusians which came close to extinction twenty years ago. The Andalusian breed has been saved by enthusiasts and we raise awareness to support donkey preservation projects.

The Iberian donkey in history and culture

If we are at the end of the long donkey history in Spain, we might ask: when did that history begin?

The donkey story is much older than historians had previously imagined. Until just ten years ago, it was thought the donkey came to Spain with the Phoenicians, roughly three thousand years ago, but remarkable archeological evidence from 2013 has shown the presence of the domesticated donkey, Equus asinus in the Iberian peninsula long before the Phoenicians arrived. Donkeys were here as far back as 2800 BC. The radiocarbon dating reliability of donkey jaws unearthed in archeological digs is 95% accurate. There is still much work to be done on this but it is now certain that the donkey has five thousand years of history in Spain: more than all the successive human civilisations that passed through Iberian history: the Celts and Iberians, the Phoenicians and the Romans, the Visigoths and Islamic and Catholic Christian empires… The humble donkey was here before all of that, and watched human civilisations come and go! More importantly, the donkeys played their working role in the construction of every phase that came and went.

The donkey still occupies a central place in Spanish culture and a good place to begin is the number of words we can find in Spanish for ‘donkey’: not just the common burro or asno. There is also: borrico, borriquillo, borrucho, buche, pollino, jumento, rucio, rucho, rozno, perico, nano, garañon… and that is before we get into the rich regional and dialect words for donkeys, including the Galician guaranho, the Basque astua, and the Catalan and Valencian ase or ruc. There are many more. The rich lexicography is a strong indication of the donkey’s central place in Iberian life and culture (just as the Inuits have many words for snow) and – to the Spanish – the donkey is the loyal co-worker who helped develop human economy in the peninsula.

Today I will go one step further and propose to you that Spain is the European country that has been most centred on donkeys as a cultural reference point. Where else in Europe do you see a sticker on the back of a car in the shape of a donkey? But there is a choice of two main car stickers in Spain: you can put a bull on the back of your car or a donkey, and in doing so you make a statement about which Spain you support. The bull sticker represents the macho Spain of cheap brandy, tauromachia, and flamenco. With a fighting toro on the back of his car, the driver is telling you he is a conquistador. With a burro sticker on the back of his car, the driver is telling you he is a humanist and symbolically standing up for the Spain of Sancho Panza, the honest working man who counts his centimos and is a realist. This burro represents España vaciada, the depopulated rural Spain of sleepy villages and glaring whitewashed walls, where the burro was a suffering beast of burden like your great-grandparents who worked in the fields. The burro sticker is a statement of stoicism: this is the Spain where nobody will answer our concerns, but we soldier on silently and shoulder our burden.

The donkey stands for a particular version of hispanismo (or ‘Spanishness’) and we can see this in the examples of Spanish literature and art that I wish to bring before you here.

Don Quixote de la Mancha

Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) is the obvious starting point for an example of the donkey in literature. I will assume your general knowledge about this novel, since all Europeans have been familiar with its two main characters for four centuries, even if they have never read the novel! As a foil to the idealistic knight, Cervantes gives us his squire Sancho Panza, a simple Manchegan peasant whose relationship with his donkey is sentimental: he demonstrates great affection for his animal. This is far from the image often associated with the Spanish attitude to animals but Sancho’s love for his donkey is entirely in tune with the audience Cervantes was writing for.

There is evidence that the relationship between Sancho and his donkey was a main attraction and we can see this in the publishing history of the book. In 1605 Cervantes published Part 1 of Don Quixote which was an immediate success. It would be nine years before he completed and published Part 2, but a revised edition of the first part was published almost immediately and the two small changes to the text are remarkable because they concern the disappearance and reappearance of the donkey.

New paragraphs were added to chapter 23 concerning the theft of Sancho Panza’s donkey and then, in added text to chapter 30, a very moving scene describing the recovery of the animal. These additions provide a far deeper characterisation of the relationship between Sancho and his donkey than existed in the first printed edition and it was the author’s response to the well-reported audience feedback. Other famous writers of the day, like Lope de Vega, showed their appreciation of the novel, but Cervantes also received popular acclaim and was aware of the elements that attracted the ordinary reader. Sancho and his donkey were universally enjoyed by readers of the novel. To the extent that public opinion was measurable, the donkey scenes were popular, so this extra material was added to the quickly printed second edition in 1605.

This additional text provided the illustrators of the novel with material for a powerful visual scene. In various illustrated versions we can see the treatment of Sancho being reunited with his donkey. For the last great Spanish history painter José Moreno Carbonero this scene was a gift. “Sancho Panza meets his donkey” painted in 1894, is a very popular painting in the Prado Madrid.

Moreno became known as the ‘painter of dust’ for his scenes of the roads in which the great blue Manchegan skies are reflected in the vast dusty camino. Sancho Panza greets his donkey and asks for his forgiveness. It is precisely that scene from Chapter 30 that was inserted into the revised edition of Don Quixote in the second printing of 1605.

We see Sancho on his knees before his ‘rucho’ – a donkey of Andalusian breed like the one you have met today (my Matilde) – and he is contrite and tearful: “Donkey of my eyes, my companion…” These are powerful sentiments but Cervantes then lends his humanism to the animal: “And the donkey remained quiet, letting Sancho kiss him and caress him without responding with a single word.”

There is a curiosity in this pose of the donkey, but it is one that any donkey keeper will notice. The position of the donkey’s tail. Raised that way, lifted horizontally, the tail tells us only one thing: the donkey is at the point of dumping two or three kilos of shit onto the road. Is that what he thinks of Sancho Panza’s apology? And is this the artist’s shared ironic secret with any viewer who really knows donkeys?

Campo de Criptana: Azorín and Sorolla

In 1905, celebrating the third centenary of the publication of Don Quixote, a young Alicantino from Monóvar with the pen name “Azorín” arrived in Campo de Criptana in La Mancha. He was one of the intellectuals of the “Generación del ‘98” who would define the new century with their art and literature. The painter Joaquin Sorolla was another of that group. Azorín wrote about rural life in Spain and his portraits of the villages and towns in the campo would become part of Spain’s new sense of itself as a nation. Geographical and sociological essays were part of the cultural contribution to a new Spanish sense of nationhood, which would eventually feed into political nationalism… but that is another story.

Campo de Criptana is a place famous for its typical Manchegan windmills and it is one place – among several – that claims to be the inspiration for the scene in Don Quixote where the knight mistakes a windmill for a giant and goes into battle attacking the windmill on horseback.

On the three hundredth anniversary of the publication of Don Quixote, in 1905 Azorín wrote about Campo de Criptana. “This is a place not of knights but of ‘Sanchos’,” he said. He described the rural life of the place and in a long description of its menfolk he explained that they described themselves as ‘Sanchos’. The squire with the donkey who accompanied Don Quixote must have come from Campo de Criptana, according to Azorín. (His articles from 1905 can be found in the collection, La Ruta de Don Quixote: 2005 centenary edition or in this online collection.)

Another of the Generación del ‘98 was the painter Sorolla, a friend of Azorín, and it is no mystery why he arrived in Campo de Criptana seven years later to create his famous painting “Tipos de La Mancha”. Having read Azorín’s description of the men of Criptana as ‘Sanchos’, Sorolla travelled there to paint two typical men of La Mancha with a donkey. Like Azorín, Sorolla was contributing to a sense of Spanish nationhood with his paintings of scenes of working life – whether on the shores of Valencia or in the villages of the interior – and giving the viewer a picture of the nation.

Sorolla painted the white donkey in Criptana in a place unchanged today: a sheltered spot at the top of the town next to a hermitage with a background of windmills. Two men in typical Manchegan clothing are portrayed together with a white donkey. They were chosen from the men of the village who had assembled in the market square and had been told to wear traditional dress in the hope of being chosen by Sorolla for the painting. The pay for two days work as models was more than they could earn in half a year. These two men – two ‘Sanchos’ of Campo de Criptana – are immortalised in the painting. In their dress and in their way of life nothing distinguishes them from the men of three hundred years previously when Don Quixote was published. This painting of 1912 captures the life of the 16th century. Sorolla may have called his work “Tipos de La Mancha”, but the Spanish public had the final say: the work hanging in a place of honour in Sorolla museum in Madrid has long been known as “El Burro Blanco”.

A Spanish donkey gets the Nobel Prize

Sometimes a book written with children in mind becomes a literary classic, like Alice in Wonderland or The Little Prince, and in the case of writer and poet Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881-1958) a little book written in 1914 was part of his work that won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1956.

Platero y yo tells the story of the narrator’s donkey Platero and in sixty-four short one-page chapters, Jiménez presents his brief lyrical sketches of a world seen through the eyes of the small donkey. These sketches have an almost zen-like simplicity and are best read as self-contained meditations rather than a continuous narrative. The childishly simple illustrations that accompanied the text in its later editions were done by the modernist artist Augustín Úbeda (1925-2007).

Conclusion

In modern Europe, Spain is the last refuge of the donkey as a cultural icon. You find donkeys all over Europe, but it is here in Spain that the donkey retains its special cultural significance. Every morning I awake to the sound of donkeys braying. This is more than the donkeys demanding their breakfast: they are asserting their place in the landscape, just as they have done for five thousand years. They were here before our civilisation but they now depend on us because they are retired, redundant workers. Many people in Spain believe we must preserve them, not just as a species but as a part of the history and culture of the country.